(EN) PLAGUE — This Shall Not Pass

Text by Alex Fisher

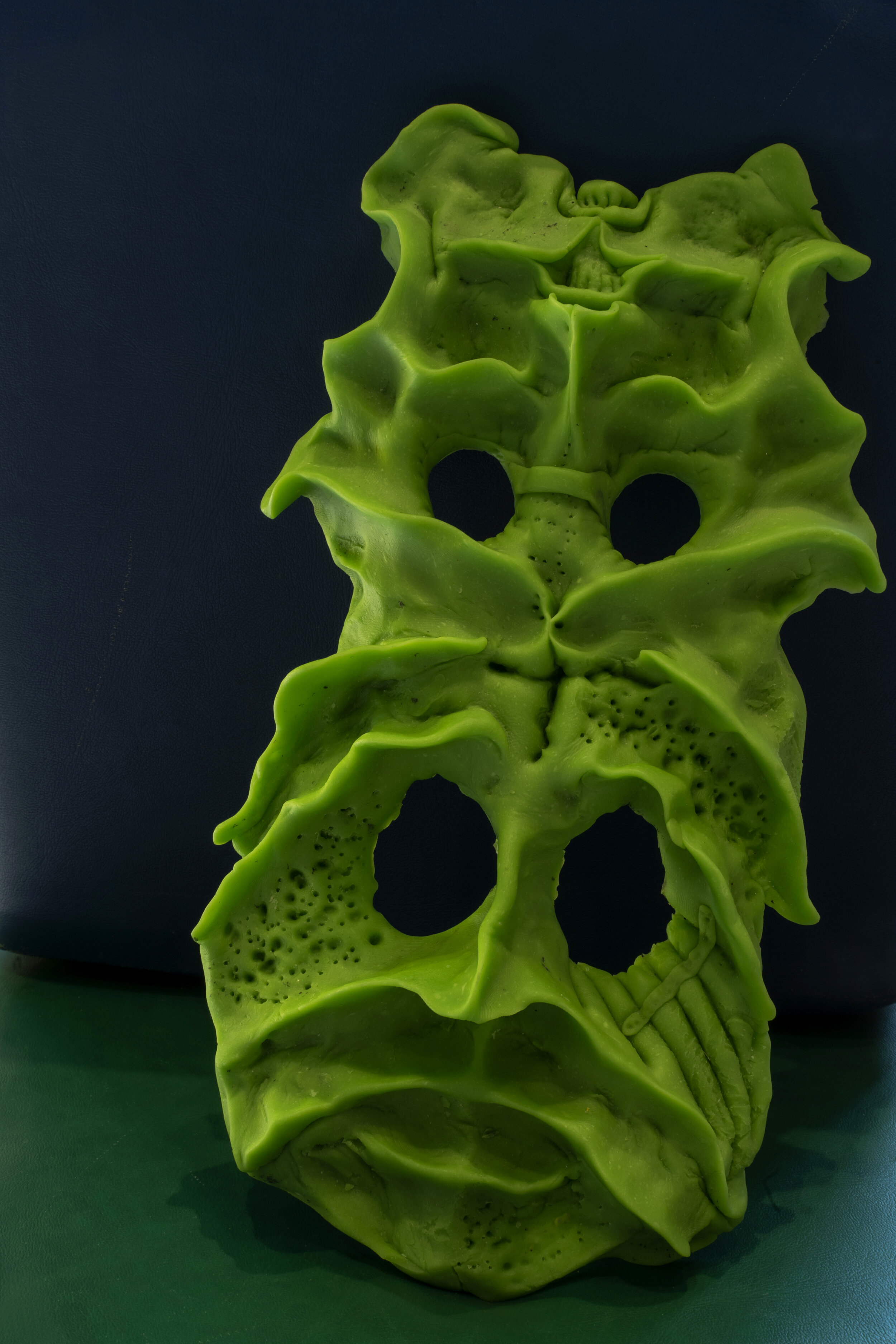

Pasha Bezor, Vanya Venmer, Arthur Golyakov, Stas Lobachevskiy, Altar I

This shall not pass.

So states a note wrapped around a zip tie dripping in wax in the Krasnodar, Russia-based curatorial group Plague’s first exhibition, 'First Blood,' staged in December 2018 in the backroom of a burger restaurant. It is an ominous declaration, simultaneously a seizing of control and a realization of forces beyond belief, all seasoned with the sardonic—horrorcore with a side of fries, ketchup, and an ice cold Coca-Cola.

The work where this missive appears, Altar I, is a joint piece by Plague’s four founding members—Pasha Bezor, Arthur Golyakov, Stas Lobachevskiy, and Vanya Venmer. Emblematic of the collective’s orientation towards the occult and the unraveling of the comfort we seek in public space, Altar I conveys that the mystic is in our midst—disembodied and viral. It is better to bow down than act blasé.

Nevertheless, the exhibition statement for ‘First Blood’ is, itself, painfully blasé —

“We came to Burger King, made our orders, sat at the table and started discussing Trump and how he won the elections.

Suddenly, I felt like I wanted some Fanta. Not Mirinda, but Fanta. I ordered some, took a sip and realised it for the umpteenth time: “that’s not the flavour I wanted.”

Trump… the world talks in circles about him. Round and around. Disdain germinates sans solution. Praise does too. For and against are propelled towards the ends of the spectrum, closer and closer to the edge. The fast food joint is an apt place for such conversations to occur—those embassies of grease, those Whopper bastions. The last time I landed in the States, I made a beeline for the airport Wendy’s. My Virgin Atlantic flight was one of the last to land that evening. The only folks at the Wendy’s were me, a troop of Portuguese scouts, and a couple off-the-clock TSA agents. The cup that came with my combo meal read “RAISE THIS GLASS TO BACON.”

The second clause of the ‘First Blood’ statement, attributed to Golyakov, is caffeinated regret for faulty impulses. These days, you can’t trust anybody, even yourself. We are left wanting, even when trying to settle on a soda. So we look to the art.

From left to right: Vanya Venmer, Untitled (2), 2018 / Arthur Golyakov, Untitled (Totem), 2018 with Pasha Bezor, Untitled, 2018

Yet the point where the setting, or stage, ends and the art begins is tricky to distinguish—a tactic which has become a hallmark of Plague’s exhibitions. One of Bezor’s untitled faces frowns on the fourth shelf of Golyakov’s Untitled (Totem), a thorn and rope-enwrapped refrigerator. Venmer’s Untitled (2), a three-tiered work that seems a dusty byproduct of a tryst between WALL-E, Ed Atkins, and Ace Hardware, is propped up against a wall covered in graffiti tags and a black-and-white portrait of a well-fed baby. The chaotic, ambiguous space between one and the other is a space of exoneration. Like that place in the forest in Idaho where you can get away with murder, Venmer exists in and exploits the potential of an extrajudicial zone.

The message is ‘this shall not pass.’ The method is teased out in Bezor’s Tutorial. Tucked in a corner next to the fire alarm, the work takes the form of a piece of scratched particle board. The bottom left quarter is coated with red tape which has then been covered by tape with a woodgrain pattern. The red peeks through tears in the imitation wood. The latter is ‘stained’ darker than the particle board, and the grain is going the wrong direction. The end of that tape is covered by a different shade of wood grain tape. The top of this layer peels back, revealing a grinning, squinting reflective emoji. His three comrades remain beneath, happy as can be. Fake nature is drowning plastic smiles. Their enthusiasm can’t be extinguished.

How many fakes does it take before fake becomes real? Before fake becomes fatal? Trees create the oxygen we need to breathe. Bezor’s tree tape covers the nose and mouth through which we breathe. What sustains can also kill. What giveth taketh away. Plauge strains the senses, but the senses they attempt to strain are those of cartoon stickers. Panic! At the office supply store.

Across Plague’s pursuits, language, predominantly English, is the smoke, the mirror, the diversion, and the directive, as with Venmer and Lobachevskiy’s Symbols of Indifference, a felted geometric on the restaurant floor. An arrow of uncertain origin spills out in a red puddle. The destination is clear, but the way there is not given and the case for going there is not made. What is left is a map without motive.

Maps are a manifestation of an urge towards movement. During the present pandemic, movement is antagonistic.

Hundreds and hundreds of millions of us have spent these last months contained. The two-room apartment I live in is blank apart from a lone wall painted Pepto Bismol pink. When I saw the apartment on the site of the rental agency, there were pictures of palm trees hanging on the wall. When I moved in, they had been removed; Kyiv was no longer Kauai. The blank nails have never bothered me more than now, but it is too close to the end to hang something on them; my lease ends in June. The nails are symbols of indifference. They are there, but they don’t care.

My bare box lacks substantive juxtapositions. Plague’s juxtapositions are abundant and communicable. Since ‘First Blood,’ Plague has organized fifteen shows in eighteen months, equating their progression with that of “a musical album whose songs are exhibitions.” The bulk of their shows-cum-songs have been in non-traditional venues, including a cocktail bar, a craggy beach in Novorossiysk, and a pizza parlour.

From left to right: Installation view, ‘Supervisor,’ Dodo Pizza / Pasha Bezor and Pasha Blagoveshchensky, Visitor (Su), 2019 / Pasha Bezor and Pasha Blagoveshchensky, Visitor (Vi), 2019 / Installation view, ‘Supervisor,’ Dodo Pizza

The pizza parlour is a franchise branch of the Dodo Pizza chain in the Black Sea town of Anapa. Plague’s July 2019 exhibition therein, ‘Supervisor,’ featured collaborative works by Bezor and Pasha Blagoveshchensky—garish doubled faces, dubbed Visitors, moulded in a rainbow of colors. The conjoined Visitors were situated in the kids corner of the restaurant, sitting atop stacked stools, reclining on pink building blocks, contemplating fate in an upturned playhouse.

In the ‘Supervisor’ installation, there is a finger lickin’ good push and pull between what it is to be entertained and what it is to be the entertainment. The Visitors are the attraction, but they appear at rest—the rooms’ plush and plastic furnishings function as sedatives, not stimuli. In the service industry, the customer is always right. Bezor and Blagoveshchensky’s intergalactic clients don’t lift a finger. They just look, loll, and lie about. And the majority have their mouths pinched shut, so they won’t be ordering anytime soon.

Encountering Plague’s portfolio, it becomes apparent that theirs is not a desire to seek the fringe. Rather, they merge, twisting themselves into our traits and our icons, especially in 'We Will,' a group show staged in the summer of 2019 at Krasnodar’s Shukhov Tower.

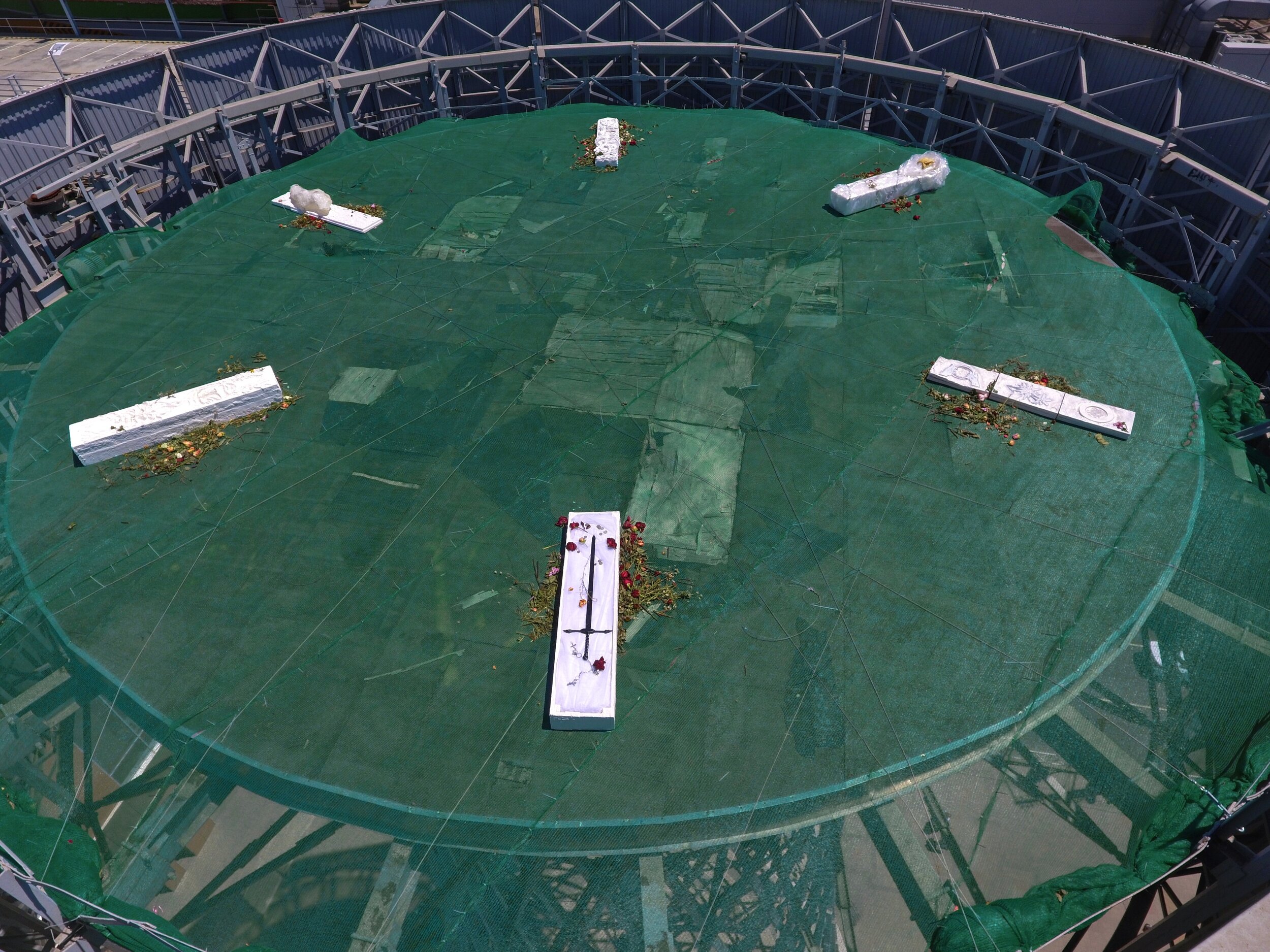

Installation views, ‘We Will,’ The High of Culture

The Shukhov Tower is a tangle of matte metal supports, polished wire, green nets, and wood planks. In their curation, Plague rechristens the Shukhov Tower as ‘The High of Culture,’ occupying its spiral stairs, sides, lungs, and scalp. Another Visitor appears in the corner of an out-of-order fuse box. Green and slimy, the ghoul frowns a prolific frown. The extraterrestrials came, and they didn’t like what they saw. This one missed the return flight.

Further along, ‘pygmalion’ is scratched out in a pen-on-paper drawing by Golyakov, Untitled (V2), taped to the tower’s supports. George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion falls in love with a sculpture of his own making, and obsessively wills her to life. Golyakov, who describes his interests as rooted in themes of “possession, repetition, self-mythologizing, and everyday rituals,” has a more tempestuous relationship. ‘Pygmalion’ is redacted; ‘RosenRot’ remains—the title of a track by Neue Deutsche Härte band Rammstein whose lyrics tell the tale of a suitor who falls to his death while searching for a flower for his beloved.

The pursuit of affection and actualization follows a path ridden with aberrations. In the case of ‘We Will,’ the pursuit is an ascent. Six mock coffins lie in state at the Shukhov Tower summit, spaced evenly like the spokes of a sundial. Snaking red hair peeks out of Nastya Vasileva’s chained plastic GAP0002. The poisonous flower Golyakov mentions in Untitled (V2) reappears in his Untitled (Zero, Legends, Strength of materials). Vladimir Omutov’s mummified block of yellow ice is sweating.

The sun shines on the cleansed casualties, and the shadows grow. The coffins are littered with wilting roses. The leader of the cohort is Venmer, whose coffin, RUR.TOD.&BRE-B.?, is topped by a black sword and coins of various origin—Georgian lari, American nickels, British pennies, etc. Attached to the hilt are handmade keychains which I think I once purchased with the aforementioned nickels at an arcade in a bowling alley in suburban Atlanta.

‘We Will’ has neither a Will nor an Executor. The authors’ assets, the coffins, are equally divided, but the audience isn’t told who gets what. Subsequently, memorialization becomes an act of observation rather than repossession. The memorialization primarily occurs on the internet; documentary images of the exhibition reveal the show’s in situ anonymity. A couple of smokers sit on the benches below and Tesla-driving prospective shoppers pull into a parking spot at the adjacent mall lot. Plague’s pyre is left to burn on TZVETNIK, AQNB, O-Fluxo, Journal and Hugo Zorn—the e-Cabaret Voltaires of a decentralized society of code-speaking curators, artists, and subscribers.

I have been listening to Depeche Mode on repeat while writing this essay; I would approximate that I am responsible for three hundred and eleven views on Youtuber Alex Nikitenko’s upload of the British band’s 2001 Paris show. Perhaps, née probably, I have become brainwashed, but I believe the chorus on “The Sweetest Condition” has bearing on the Plague effect:

“Taken in by the delicate noise /

Knocked to the ground by the subtle thunder /

Shackled and bound by the sound of your voice /

Wandering around in silent wonder.”

Plague writes that they “distrust those ways of thinking that just mark time or can’t explain global processes.” They don’t shock like a lightning strike. There are no paralyzing jolts of energy. But the voltage is being ratcheted up. All of a sudden, the storm is overhead.

Last November, I visited 'Better don’t touch it,' a group show curated by Plague at the invitation of Anna Teterkina at Moscow’s ISSMAG Gallery. It was a brutally cold Sunday. Judging by the empty sidewalks, it was apparent that most Muscovites were in voluntary lockdown. I couldn’t blame them. Why bother venturing out when it is fourteen below? Why would you want to hear your bones creak and crack?

From left to right: Stas Lobachevskiy, Reaching out back, 2019, Installation view, ‘Better don’t touch it,’ ISSMAG Gallery

Plague’s greeting was, as to be expected, frigid. The lighting, designed by Maria Krikun, was deep blue with blips of hazard red. In the front right corner, Lobachevskiy’s wrinkly Reaching Out Back was coming undone. An experiment had gone wrong, or it had gone frightfully right. Vasileva’s GAP005, an oil-slicked suspension of hair, chains, and mirrors, hung in the opposite corner. The ooze had frozen. If a match was struck, the congealed ooze would alight and the knotted work would be consumed in flames.

A split second later I would be too. Then you.

-

Text: Alex Fisher

Photos: Courtesy Plague, all rights reserved